The Balfour Declaration, Britain’s World War I commitment to support the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine, is without doubt one of the most influential political documents of the 20th century. Incorporated into Britain’s Mandate over Palestine at the war’s end by the newly created League of Nations (and thereby guaranteed under or sanctioned by international law), the declaration was the guiding principle of British rule for thirty years. The ultimate realization of the Balfour commitment in 1948 with the creation of Israel changed the face and history of the Middle East.

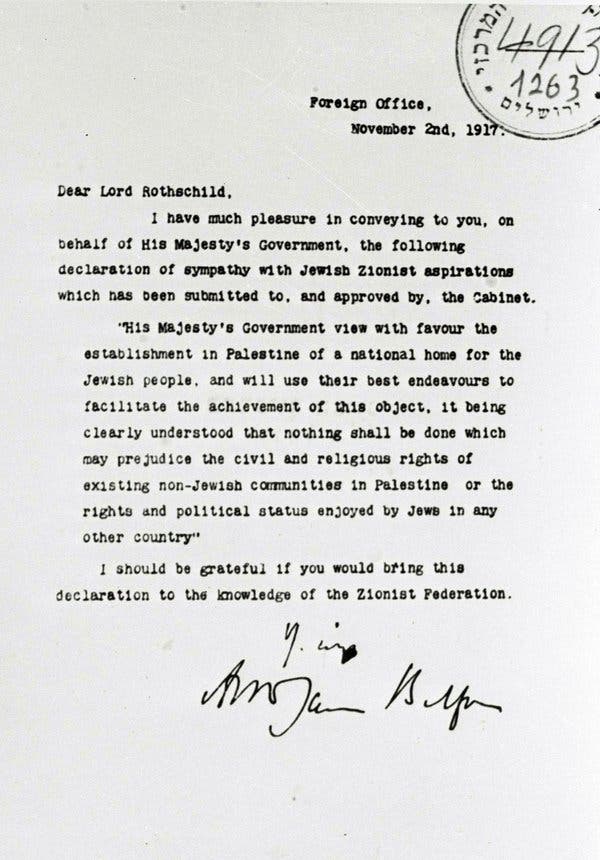

The declaration took the form of a short letter dated 2 November 1917 from Lord Arthur James Balfour, British Foreign Secretary, to Lord Lionel Walter de Rothschild, head of Britain’s Jewish community. Approved by the British cabinet, the statement reads as follows:

His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

The statement was the product of Zionist advocates inside the government (including Balfour, Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and cabinet member Herbert Samuel), and from outside; of paramount importance was the immensely energetic and persuasive Zionist spokesman Chaim Weizmann, who had longstanding close relationships with Balfour, Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, and other powerful figures of the political elite. From a strategic perspective, British officials hoped that taking a “favorable view” toward a Jewish national home in Palestine would garner Jewish support in the United States, Germany, and Russia, thus bolstering the war effort. They also sought to solidify postwar British claims to Palestine to shore up control over Egypt and the Suez Canal.

The declaration was conceived and drafted in the heat of World War I, when Great Britain and France, anticipating an allied victory over the German-led Central Powers, were thinking ahead to the postwar fate of the Ottoman Empire’s Arab provinces. The two Western powers had already negotiated (with Imperial Russian approval) the division of the Arab provinces into French and British spheres of influence, with Lebanon and Syria to be under French control and Iraq, Transjordan and part of Palestine (Acre-Haifa region and the region from Gaza to the Dead Sea, including the Negev) under British control. The rest of Palestine was to be under international administration. The secret treaty—the so-called Sykes-Picot Agreement—was signed in May 1916 but made public only in November 1917 after the Bolshevik revolution. Meanwhile, Sir Henry McMahon, Britain’s High Commissioner in Egypt, had secretly promised Sharif Hussein of Mecca, leader of a pan-Arab national movement, that Britain would support Arab independence after the war. This promise (which was directly contradicted by the promise contained in the Balfour Declaration) helped secure the support of Prince Faisal, Husayn’s son, who led an Arab military force in a revolt against the Ottomans in June 1916.

Shortly after the declaration was issued, British troops entered Palestine, capturing Jerusalem in December 1917. Occupation of the entire country was completed by October 1918, and military government was imposed. Preparations were immediately made to start implementing the Balfour Jewish National Home policy. Less than two years later (and before Britain was formally assigned the Mandate over Palestine), Sir Herbert Samuel, an avowed Zionist, became Palestine’s first High Commissioner, and in August 1920 the first immigration ordinance was passed by the new Civilian Administration, opening Palestine to Jewish immigration.

The 1919 Paris Peace Conference had established the League of Nations and introduced into international law the concept of “trusteeship” known as the Mandate system. As described in Article 22 of the League’s covenant, territories of the defeated nations would be tutored by “advanced nations” on behalf of the League until they could stand alone. Specifically, Article 22 recognized the formerly Ottoman Arab provinces as “independent nations” subject to the administrative assistance of a Mandatory power. Although the League’s covenant stipulated that the wishes of the communities “must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory,” the Mandate for Palestine was granted to Britain at the San Remo Conference in April 1920 and imposed on the Palestinians.

The text of the Mandate for Palestine, approved by the Council of the League of Nations on 24 July 1922, comprised a preamble and twenty-eight articles.

The preamble reiterated Britain’s commitment to the Zionist project in the terms used in the Balfour Declaration, but presented a justification that was not explicit in the Declaration, i.e. its “recognition” of “the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine”. Concerning the vast majority of Palestine’s population (almost 90 percent according to the British census of 1922), primarily Christian and Muslim Arabs, the preamble referred to them, similarly to the Balfour Declaration, as “the non-Jewish communities in Palestine,” declared that nothing would be done to prejudice their “civil and religious rights,” and made no mention of their political or national rights.

In contrast to the short and restrictive reference to Arab rights in the preamble, the operative text of the Mandate was replete with Britain’s various responsibilities to foster the Zionist project in Palestine: Article 2 made Britain responsible “for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home”; Article 4 recognized the Zionist Organization and its subsidiary, the Jewish Agency, as the body responsible for “advising and co-operating” with Britain on all matters that “may affect the establishment of the Jewish national home and the interests of the Jewish population in Palestine” (no such body was recognized for the majority population); Article 6 pledged Britain’s commitment to “facilitate Jewish immigration” and to encourage “close settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands not required for public purposes”; Article 7 emphasized the inclusion in new nationality law of “provisions framed so as to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews”; Article 22 gave Hebrew equal status with Arabic as an official language in Palestine; and so on. The Mandate formally went into force on 29 September 1923.

From the start, the Arab population of Palestine expressed their opposition to the Balfour policy in numerous ways, including demonstrations and violent clashes in April 1920 and May 1921. Opposition to the Balfour Declaration dominated the agendas of meetings of the Palestine Arab Congress (held in January–February 1919, May 1920, December 1920, June 1921, August 1922, June 1923, June 1928) and the delegations that it dispatched to London (from August 1921 to July 1922; July 1923, and April 1930). The relentless Palestinian opposition prompted British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill’s White Paper of 1922, which sought to clarify that Britain’s intention was to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine, not to turn the entirety of Palestine into such a home—a clarification that did nothing to mollify the Arab majority. Successive commissions of inquiry (the U.S. King-Crane Commission of 1919, the British Palin Commission of 1920, the Haycraft Commission of 1921, and in fact the entire procession of British Commissions to the end of the Mandate) all found overwhelming Arab opposition to the Balfour policy and what it entailed.

Within this framework, the Palestinian Arab population was significantly handicapped in any effort toward independence. Indeed, any movement toward proportionate representation within the administration or policies that reflected the will of the majority was seen by the British government as an abdication of its commitment to the project of building a Jewish national home in Palestine. The tension between the self-determination promised by the League of Nations and the Mandate’s privileging of the national aspirations of a largely foreign minority was a continual source of conflict and dissatisfaction throughout the Mandate period, as was the transformation wrought by the influx of Jewish immigrants and the development of Zionist institutions. While Britain’s other mandates received nominal independence (Iraq in 1932, Jordan in 1946), the Palestine Mandate put in place structures that allowed the Zionist movement to gain the upper hand over the indigenous population, leading in 1948 to its displacement and dispossession rather than its independence.

From 1918 to 1936, Arabs throughout Palestine have commemorated 2 November, Balfour Day, as a day of mourning, marking it by demonstrations and one-day general strikes (brought to an end by the British suppression of the 1936 revolt). Meanwhile, the Jewish community of Palestine proclaimed 2 November a national holiday, which was celebrated from 1918 to the end of World War II. Given the faltering prospects of the Zionist project in 1917 and the facts on the ground, it is not too much to say that without the Balfour Declaration there would be no Israel.